Nora Miller is a death with dignity advocate in Phoenix, Arizona.

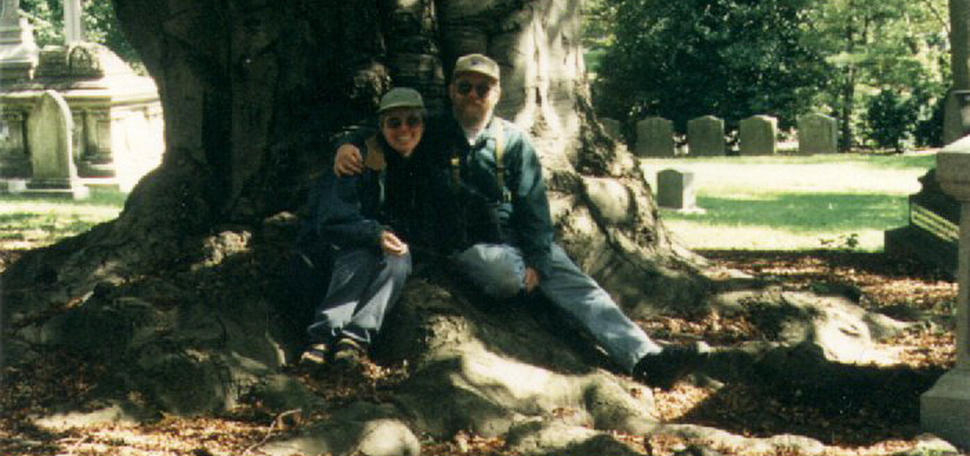

My husband Rick and I talked about death with dignity in general terms in 1996 when my mother died in pain and struggling for breath, and then again during the debates and publicity around the 1997 ballot initiative on Oregon’s law. We both agreed we’d prefer to control the conditions of our own deaths.

In early 1999 Rick developed a cough that wouldn’t go away. The diagnosis of metastatic terminal lung cancer in April left no room for doubt or hope for something less final. His first words were, “Now we are going to Alaska.” (Alas, we never made it.) His next words were, “I will be using the Oregon law.”

We were fortunate our son and both our families supported his decision, with some regret and a few reservations, but without argument or complaint.

By mid-October, the doctor suggested it was time for hospice. We were able to keep Rick at home. Later that month, Rick made his first oral request under the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, followed by a written request, and the final verbal request in early November. Rick’s oncologist had never received a request before—with the law only two years old, everyone was new at it—but he was reasonable and sympathetic. He agreed Rick was of sound mind, not depressed, and definitely terminal. He wrote the prescription on a cold, rainy Friday in early November, and I drove across Portland to the only pharmacy willing to fill it at the time.

Rick told me he thought he’d be a lot sicker when he’d be making the decision to use the prescription. He was, in fact, a lot sicker than he thought. He was having trouble with his voice and with swallowing. He often lost words or used them seemingly at random. He woke up with blinding headaches from a growing brain tumor. He couldn’t walk on his own. He’d become emaciated.

The day he made his decision had been a hard one: he was very tired and weak, and medications had deprived him of his emotional control. He was ready to go. I challenged his intention. I told him he could sleep on it, decide the next day. He was sure. He was calmer than he’d been in weeks, almost jovial, relieved. He needed the control and the ability to choose, and he needed to know that, in the end, we’d have joy and love in the midst of our sorrow.

This was a last loving gift we gave each other. I wanted nothing more than to make that possible for him. I’ve never once regretted it. I’ve often replayed those last weeks, recalling moments where I could’ve or should’ve done something differently. It’s taken me years to understand what I did was what Rick wanted, and to have done anything different would’ve made the process about me and not about him. It was his life and it was his death—he needed the right to decide how it would happen. To provide real dignity in dying, we must unconditionally respect the unique and inherent personhood of the person at the center of the process.

Nobody’s death with dignity story will be the same as mine. The dignity people seek in the dying process is unique to them. For some, it’s a time to reconnect with old friends and heal old wounds. Others need a few close friends who can help them address their fears and assess their options. For others still, it means focusing on the narrowing possibility of recovery, of beating the odds. But for every single person who is dying, Death with dignity means having the right to continue to be the person they’ve always been.

I’ll be forever grateful to my fellow Oregonians for making this possible for Rick. I just hope the remaining 47 states join Oregon, Washington, and Vermont and enact similar laws soon.