Glenn Church is a farmer and businessman in Royal Oaks, California.

From a very early age, I remember my father Warren talking about how he wanted to die. He would tell me, “If I reach the point in life where I can’t do what I used to be able to, if the end is coming, I hope there’s a way that I don’t have to suffer and feel useless.”

When the California legislature passed the End of Life Option Act two years ago, he said, “If my health declines and I have a chance to use the law, I will.”

Declining Health

In May 2016, my father’s health began declining dramatically. A series of health issues stretching back several years had begun to catch up with him.

I had noticed that he’d been losing weight. We took him to an oncologist, an internist, and a neurologist; they did a number of different tests. They could not determine whether he had an aggressive infection or whether he had cancer. But whatever was eating away at him was spiraling out of control. He dropped 30 pounds in three months. He felt useless. If you knew my father, you’d understand. Hard work was a core part of his identity.

Death with dignity is about choice. Just as no one should be able to tell someone how to live their life, no one should be able to tell someone how to end their life either.

A Life of Hard Work

My father was born in 1929, at the onset of the Great Depression. The son of a Kansas corn farmer and a California beekeeper, he spent the first few years of his life selling popcorn and honey to the denizens of the shantytowns known as “Hoovervilles” in California’s Salinas Valley: the setting for John Steinbeck’s Depression-era classic, The Grapes of Wrath. He learned early on just how many poor people there are in this world, and how there was always some family worse off than his.

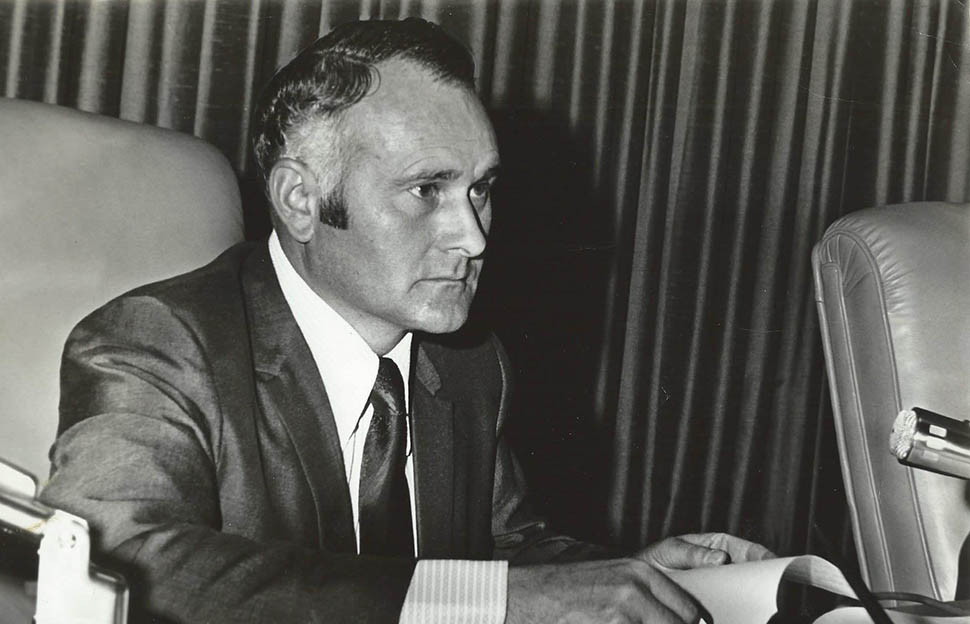

He also learned the value of hard work, which he would carry with him throughout his life: during his service in the Korean War, for which he received a Purple Heart; during his tenure as a highly regarded elected official on the Monterey County Board of Supervisors; and in his role as the owner of several choose-and-cut Christmas tree farms, where he greeted customers warmly during the holiday season.

He could work 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, and be ready for more. He was an extremely dynamic, extremely motivated, disciplined person. That kind of dynamic nature stayed with him throughout his life. Which is why it was so difficult for him when his body began to fail.

Three Criteria for Dying with Dignity

He was hospitalized in July 2017. The week before his hospitalization, he could still drive on his own; shortly after he was released he couldn’t walk by himself. His appetite decreased; he was wasting away. We weren’t sure if he would last another two weeks. We arranged for hospice care. He could not do anything on his own. It was torture for him, and painful for us, too.

When it came down to it, my father had three criteria for when he knew he wanted to die with dignity. If he felt like

- he wasn’t the person he used to be;

- he was being a burden to his family; and

- the cost of keeping him alive was an undue burden on society

he would be ready to end his life on his own terms.

We had been told by doctors that my father had very little time left. He was considering voluntarily stopping eating or drinking (VSED) as his only option, because it was difficult to find doctors familiar with the requirements of the still-new End of Life Option Act.

Working with the California End of Life Option Act

Once we found doctors who did work with patients who wished to use the law, we had to wait for them to perform an evaluation to determine whether my father’s condition qualified as a terminal illness. To our relief, the doctors determined that my father’s ailment—cachexia, or wasting syndrome—made him eligible for death-hastening medication. My father made his wishes known clearly and unequivocally. The doctors respected his choices.

Death with dignity is about choice. Just as no one should be able to tell someone how to live their life, no one should be able to tell someone how to end their life either.

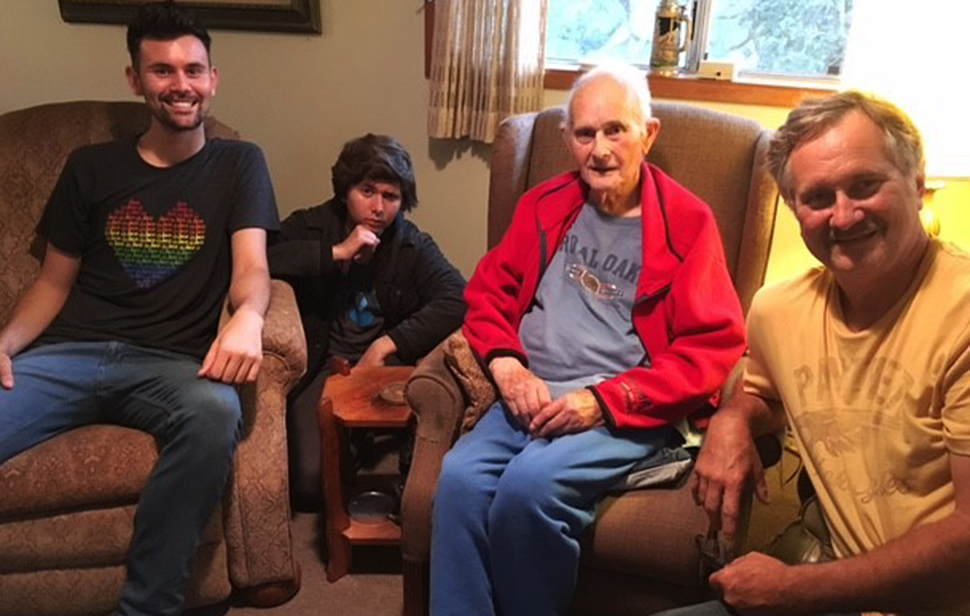

His final weeks were a tumultuous mixture of joy and pain. We reminisced about the good times in his life; watched him devour seemingly endless amounts of cake and pie; and came closer together to support him.

But his health took a turn for the worse, and we did not yet have the medication. The three days we had to wait for the pharmacy to receive a shipment of the medication were excruciating. But once my father had the medication, he was more at peace; he knew he had control over his final days.

A Calm and Peaceful Death

When the time came, on a hot day in September 2017, two of my father’s caretakers emptied the contents of the medicine into a cup of orange juice. He drank the bitter liquid, then I gave him another glass of straight orange juice to wash down the unpleasant taste. After a few minutes of drowsiness, he started to slip away, first falling asleep, then losing consciousness. His death was calm and peaceful, just as he’d planned.

The death of my mother and father were very different. When my mother’s weight began to drop and her strength left her, the staff at the convalescent home where she lived called me in. Despite the fact that my mother had made clear her wish not to be force fed to keep her alive, a group of eight staff members tried to pressure me into giving my permission for them to put in a feeding tube. I told them, her only enjoyment in life right now is eating ice cream. You want to take this away from her? They stressed that she would die if they didn’t insert a feeding tube. “I understand,” I said. “But this is just prolonging her suffering.” They frowned at me, making clear their disgust at my decision to let my mother die.

My mother continued to suffer for some time. If she had had access to the California law, she could have had a different death. My father was able to make his own decision about how and when he wanted to die.

We have received an overwhelming amount of support for my father’s decision. We have not encountered anybody who has said how evil and wrong this was, including a number of very religious people who might have been philosophically opposed.

I was not active in campaigning for the End of Life Option Act, but I now want to share my experiences with as many people as possible. Through media interviews and other conversations with engaged citizens, I am committed to relaying my father’s story. People need to know that this compassionate option is now available to all qualified Californians.