Update: the Maine Death with Dignity Act passed in 2019.

Cayla Miller is a mother and library events coordinator in Belfast, Maine.

My mom, Eva Thompson, didn’t want to die. My mom was dying from metastatic colon cancer. There is an essential and fundamental difference.

In my selfish love for her I wanted to steal every second with her that I could, but if I could have spared her those last few days of lying helpless and in pain, I would have.

I don’t consider that suicide. And I know she did not either.

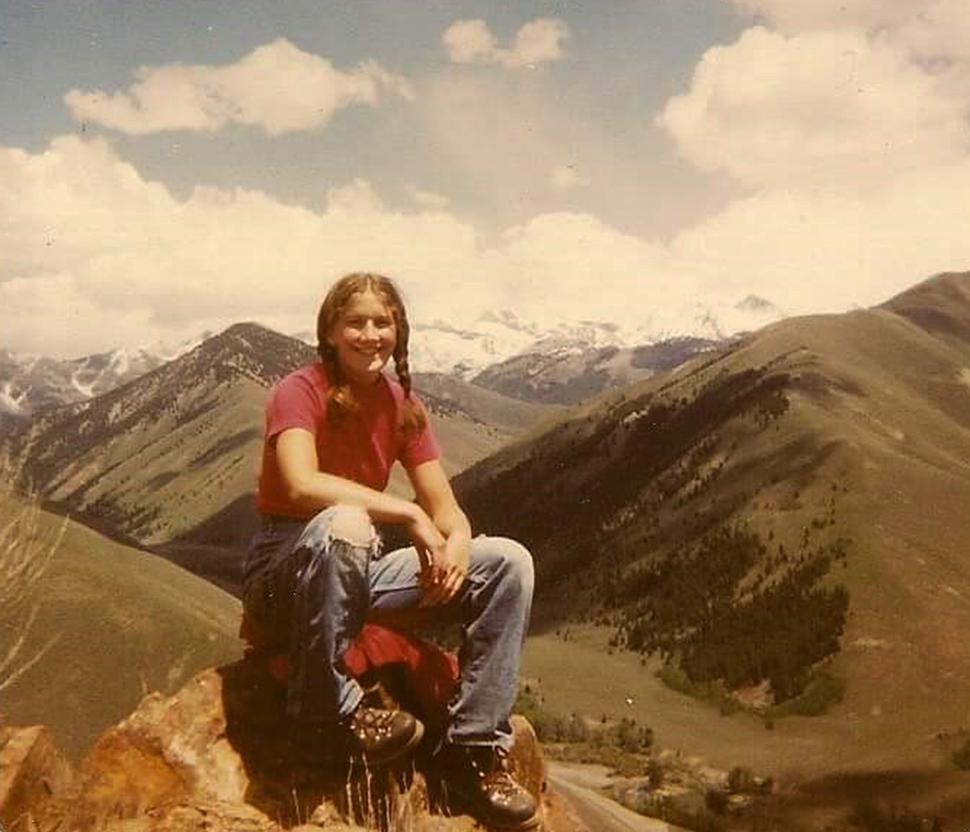

An Artist, an Explorer, a Nature Lover

Before the cancer took her far too soon, my mother was a vibrant, strong woman who treasured her family and found joy in nature and in making art.

She especially enjoyed when the two intersected, as when she was carving soapstone bird sculptures outdoors, or making concrete impressions of leaves, or making life-sized plaster birds in the kitchen.

She loved to experiment with art materials. A staple of my childhood was trying some new “project” with her. She sculpted with plaster strips, made us elaborate piñatas, folded paper stars, and let us roll giant sheets of paper across her kitchen floor to color on. She made our Halloween costumes and helped us with whatever crazy project we decided to try. She helped me when I had the crazy whim to try to make/sew/sculpt my own wedding dress. It didn’t work out, but she went all in trying to help me create the dress I envisioned.

She encouraged us to read, to explore, to do art, to be in nature. She let me backpack through Europe at 18 by myself, which, now that I am a mom, I understand must have been excruciating. She and my dad showed me what a good marriage looked like, from their “engagement canoe” (more practical than a diamond!) to their quiet, strong partnership my whole life.

It would be a huge relief to know I have some control over how the ending goes. It should be my choice to die quickly and painlessly when I decide the time is right.

Eva Thompson (1959-2017)

Illness And Advocacy

My mother was diagnosed with metastatic colon cancer in 2013, just a month before my wedding. She kept her views on assisted dying laws very private at first, only mentioning offhand that she had been to Augusta and was lobbying. She was such an independent soul, she didn’t get into a lot of detail at first.

My mother and I discussed death with dignity a number of times. Once I understood what it was, and what it meant for those suffering from a terminal illness, I supported her fully in her desire to die with dignity. This is the kind of decision a person must make for themselves, with no other input. What right do I hold over my mother’s life, or that of a stranger?

As she saw her family supported her, she was more open about her beliefs. I am so proud of the work she did with Death with Dignity National Center and her fellow Mainer, Valerie Lovelace, to share her story and raise awareness about the need to provide terminally ill Mainers with greater end-of-life options.

We all want to spend every moment we can with someone who we know is dying. It is terrible to say goodbye. But there is no real goodbye when your loved one is comatose or delirious. Mom didn’t want to be helpless, she didn’t want to be in pain, she didn’t want to linger in uncertainty. And, I know she wanted to spare us the added trauma of watching a difficult death. Unfortunately, it was not a choice she got to make in the end.

A longtime hospice chaplain volunteer, my mother was intimately acquainted with the details of end-of-life care. When her own end drew near, she took charge of her own hospice care. We always joked that if anyone was prepared for this, she was.

She left us checklists and instructions for how to prepare her body and who to call when the time came and even wrote us notes on what to say to the cremation people. She put this all in a neat yellow folder marked “I.C.E” (In Case of Emergency) and the first line read something to the effect of “Do Not Resuscitate OR I WILL HAUNT YOU!”

The Final Days

She was very clear from the get-go that if she was not able to eat, breathe, or take care of her own hygiene, she was done. As it happened, she did have to go three days in a comatose state. Her best friend from childhood is a nurse, and she was able to sit with us through that first long night and help me to bathe her.

Those last three days were not living. She was not conscious.

There were no deathbed revelations or profound conversation as you see in the movies. Instead, she was jaundiced, she was unable to eat, she was unable to move on her own.

My mother, the most private and independent person I knew, had to be bodily lifted and bathed, have water dripped into her mouth, and her pain kept at bay by morphine she was unable to ask for.

I know those last three days would have been galling to her if she had been aware. Her last word was “Self!” as she took control of the popsicle my brother was trying to feed her. I think that would have been the moment she would have chosen to take medication to hasten her death, had it been available.

We could have said our goodbyes, and held her hand as she passed. Instead, we found ourselves in limbo as she lingered, unsure if she was in pain, or if she’d ever come back to consciousness. We were unsure when the end would come, and unable to sleep as we watched her labored breathing.

Beyond Modern Medicine

While to us her pain did not seem extreme, we will really never know. Others are not so lucky, and end their days in unthinkable pain.

I’ve heard the objection that we just need better hospice care. But we had the most fantastic hospice care. They came to the house, coached us through how it might go, and what to do. They were only a phone call away. We had any medication she could have needed, we had hospital-grade equipment delivered to us. Still, it was not enough.

Sometimes, the degree of a person’s pain cannot be addressed by modern medicine. We need to understand that in some cases, as the law in Maine stands now, there is no way to make it better.

I know that many of the objections to Death with Dignity come from a place of faith. This includes some of my own family, whom I love and respect dearly. I know theirs is a strong and deep conviction. To these objections, I say I do not see a difference in medicating a dying person with morphine and letting them end their suffering a few days early with this medication. Prolonging their decline is not compassionate.

Death with dignity is allowing a dying person to make their own decision at the very end of their life.

My mom often said that her life was precious. And she wanted to spend as much time with her grandchild—my 2-year-old son—and her family as she could. But she also knew that at some point her own quality of life would be gone, that she would suffer, and that she wanted the right to control those final days on her own terms.

Honoring My Mother’s Memory

I pledged to her that I would help to pass this law so others who were suffering would be able to have their choice. That is why I am working with Death with Dignity National Center and Maine Death with Dignity on their campaign to place an assisted dying measure on the 2019 ballot. I was proud to be the first to sign the ballot measure petition and am committed to gathering signatures from Mainers around the state who want the freedom to decide how they die.

I am doing this for my mom, and for all those like her. It is how I choose to honor her memory. I know that nearly 75 percent of my fellow Mainers support death with dignity. I will work to make sure their voices are heard. When we vote together to make assisted dying a reality for our state’s terminally ill residents, Maine will become the eighth jurisdiction to authorize this essential end-of-life option.

I pledged to my mom before she died that I would help pass an assisted dying law so others who are suffering would be able to have a choice to dies with dignity. It is how I choose to honor her memory.

I am honored to be a part of the death with dignity movement. Join me in working to ensure those suffering from a terminal illness have peace, comfort, and control in their final days.