To commemorate the 25th anniversary of the passage of Measure 16, the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, we are featuring interviews with those who in 1994 campaigned for and supported Measure 16. Today we are featuring former Oregon Governor Barbara Roberts, one of the state’s most accomplished politicians and the first woman to be elected Governor of Oregon.

Between 1987 and 1991, Robert’s late husband, Frank, introduced three bills to legalize assisted dying before his death in October 1993. His efforts paved the way for the successful campaign to pass the Oregon Death with Dignity Act in November 1994 and defeat the effort to repeal it in November 1997. Roberts continues to advocate for death with dignity nationwide.

*

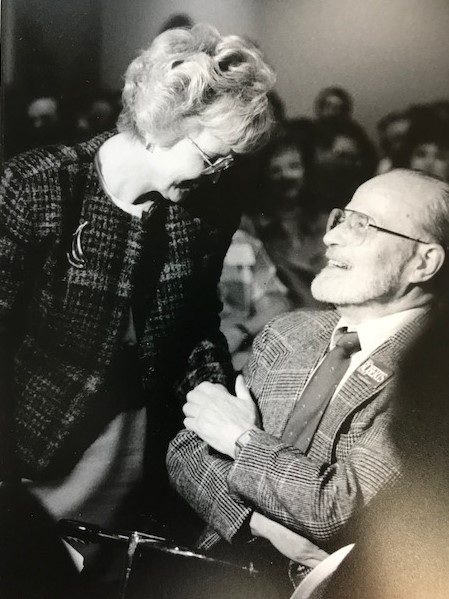

Barbara and Frank Roberts occupy a storied place in Oregon‘s political history.

Frank Roberts, a university professor, served in the state House of Representatives from 1966 to 1970 and in the state Senate from 1975 until just before his death in October 1993, making him Oregon’s longest-serving legislator at the time.

Barbara Roberts’ resume is replete with firsts. In 1983, during her second term in the Oregon House of Representatives, she became the first woman to serve as Majority Leader. In 1985, she began her first of two terms as Secretary of State, the first Democrat elected to the position in over 100 years. And in 1991, the people of Oregon elected her their 34th Governor, the first-ever woman to hold the position in her state.

Standing Up for Her Son

The former Governor has been a champion of many causes over the years. Over a decade before she held statewide office, she began her involvement in politics as an engaged citizen, successfully advocating in the state legislature for the passage of a bill to protect and expand the educational rights of disabled children like her autistic son, Mike Sanders.

“I recognized for the first time that I had the ability to change people’s’ lives through the political process,” Roberts recalls. “I developed a new attitude about my responsibility to do that.”

She served on K-12 and community college boards, pushing for improvements in education. During her time as Governor, she was a staunch advocate for gay rights and she worked to increase the number of women in state politics.

To this day, Roberts continues to campaign for a deeply personal cause: the right of all Americans to die with dignity. Her advocacy is driven by Frank’s dedication to passing a law to legalize physician-assisted death, as well as her experience caring for him during the final stages of his battle with cancer.

When Barbara Met Frank

Roberts met and became good friends with Frank in 1971, when he worked with her to pass a bill to allow disabled children to attend public schools in Oregon. Over time, their friendship had deepened into love. In June 1974, they married.

Roberts worked on Frank’s staff for Frank in the Statehouse from 1975 to 1979. In 1980, she ran for a seat in the Oregon House of Representatives and won, launching her remarkable 15-year run in state politics during which she would serve as a legislator, Secretary of State, and Governor.

While Roberts was running for her second term as Secretary of State, Frank was fighting a fierce battle with prostate cancer. Diagnosed in 1987, by 1988 Frank was confined to a motorized wheelchair after radiation treatment injured his spinal cord and destroyed the nerves in his legs.

As he adjusted to his permanent disability, Frank drafted legislation that would allow terminally ill individuals the right to end their lives in a humane, painless, and dignified manner. He believed all Oregonians should have the opportunity to decide for themselves what treatment they wanted at the end of their lives.

In 1987, 1989, and 1991, Frank introduced bills that sought to legalize physician-assisted death in Oregon. Roberts initially was hesitant to become involved with such a controversial campaign.

“I wasn’t in disagreement with the philosophy, but I wasn’t sure he wasn’t making a mistake politically,” Roberts says. “This would be so controversial that he would be attacked by church groups, and that could maybe harm his political future. But that never mattered to Frank. His public service was never about the next election.”

“The Legislature, however, had no intention of having hearings on his bill,” Roberts adds. “So really it didn’t matter what I thought or did. Frank had more influence in the Senate that I did and even he couldn’t get a hearing.”

Despite his personal battle with cancer, Roberts insists that when Frank introduced his first bill, “He was not doing this for himself. He was doing this because he really believed that end of life wasn’t being handled well by our culture, not with the respect it deserved, not with the attention it deserved, and certainly not with the compassion it deserved.”

When he subsequently introduced bills in 1989 and 1991, Roberts became vocally supportive.

Former Oregon Governor Barbara Roberts speaks about what inspired her husband, the late Oregon lawmaker Frank Roberts, to introduce a death with dignity bill multiple times before his death in December 1993. (Footage by Dawn Jones Redstone/Hearts+Sparks Productions)

“The World Changed”

Frank’s commitment to end-of-life choice never wavered, and in late spring 1991 his colleagues granted him what Roberts calls “a courtesy hearing” on the bill.

“I remember sitting in that hearing room that day, watching people testify. Frank understood this hearing meant, for the first time, they would see who stood where.”

According to Roberts, the hearing was a watershed moment.

Supporters, both citizens and legislators, emerged as the hearing progressed. Supporters now understood they had allies.

“It was the first time some of [the legislators] who supported it knew that other people they knew supported it,” Roberts says, “At the time, people didn’t talk about the legislation. It was too controversial, so people just kept their mouths shut. But that day in that room there was no question that there were some strong advocates in support of Frank’s position.

“At that point, the world changed,” she adds. “People became aware that there were other prominent and important and caring citizens who did care about it. I think it really changed the whole complexion of the debate.”

From that initial hearing grew a group of dedicated advocates that, along with other engaged citizens from the legal, medical, and political communities launched the campaign that would lead to the passage of Measure 16, the Oregon Death with Dignity Act.

Geoff Sugerman, a speechwriter for Governor Roberts, was hired by Measure 16 co-author and Death with Dignity National Center founder Eli Stutsman to be the campaign director for Oregon Right to Die, the Political Action Committee (PAC) that worked to pass the law. Barbara Coombs Lee, a registered nurse who staffed a state Senate committee on which Frank served, would become a chief petitioner for the law.

The ballot initiative campaign launched in early 1993 and quickly gained the attention of the news media and the Catholic Church, which would become—and still is—the staunchest and best-funded opponent of physician-assisted death nationwide. Oregon Right to Die was outspent by opponents and faced the formidable challenge of convincing voters to support a highly controversial issue. But they also had high-profile supporters in the political arena and in the medical community. Roberts was one.

Frank’s Final Days

As governor, Roberts endorsed Measure 16 and became a vocal advocate for the law. As Frank’s spouse, she had become increasingly involved in his care in the wake of his September 1992 diagnosis of terminal lung cancer. By the time he finished his final term in the Legislature in September 1993, Frank had entered hospice care.

“Frank was so clear that he wanted to die at home,” Roberts says. “He did not want to go back to the hospital; he’d made his decision about no more treatment after he got his terminal diagnosis.”

Roberts had the seemingly impossible task of performing her duties as governor while being a caregiver for Frank. Fortunately, she was able to lean on the hospice staff, for whom she holds deep gratitude, and trusted friends for help.

“I had a baby monitor in that bedroom where Frank was sleeping so I could hear him if he stirred or was having difficulty,” Roberts recalls. “I was getting out of bed all night long to check on him. “[My friends] said, Barbara, you can’t keep doing this. So they started helping by staying all night and sleeping in Frank’s room and being there for him. That made a huge difference, because they allowed me to get enough rest so that I was functional in my work, but also functional in my personal life.”

As difficult as it was for Roberts to absorb her imminent loss, she knew that the only way she could summon the strength to support Frank in his final days was by facing death head on.

“If you want to care for someone who is dying and maintain any kind of mental health, you have to accept that death is real, that it is coming, and that you’re going to make the rest of your loved one’s life as comfortable as you can,” Roberts says. “We tried to do everything we could to give him as much dignity and as much support as we could. Once he couldn’t use his motorized wheelchair anymore, we got it out of the room so it was never visible to him again. It went down in the basement because we never wanted him to look up and say, ‘I used to be able to get around.’”

“He liked music, so we played music. He had a music box that he sometimes played because it was quiet and it took away the sound of the oxygen tank. We kept his bed positioned so that he could see out the big windows in his bedroom. We had bird feeders out there and he liked to see the birds at the feeders.”

Even as his condition worsened, Frank continued to follow the Measure 16 initiative petition campaign.

“Often in the early part of his being bedridden, he would say, how is the signature collection going? How is our petition coming along?” Roberts says. “And I’d say, oh, Frank, they’re just gathering so many signatures. It’s clearly going to make the ballot.”

“He would say, if this measure gets on the ballot, the people of Oregon will pass it. He was always convinced of that.”

But Frank never got the chance to see his work come to fruition; nor did he have the opportunity to use the end-of-life option he championed for his constituents and for all Americans. He died on October 31, 1993, with Barbara by his side.

In her book, Death Without Denial, Grief Without Apology: A Guide for Facing Death and Loss, Roberts recounts her final moments with Frank, and the grief and numbness that followed. It is a heartbreaking story, yet even in the midst of her pain, Barbara found solace in the support of those who had shown her kindness and given her strength during Frank’s final stage of life:

I would not trade this painful, remarkable human experience for anything. I am so grateful for what Frank gave me, for what hospice helped me to understand and endure, and for the learning and growth I received from each person who was part of our journey.

Victory at the Ballot Box

As Frank predicted, Oregonians did vote to give terminally ill patients the right to die on their own terms, with dignity and control. On November 8, 1994, the Oregon Death with Dignity Act became the world’s first assisted-dying law. Supporters were jubilant; Barbara was proud.

After Roberts completed her term as Governor in 1995, she accepted a position at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Despite her relocation and shift in focus, Roberts continued to support the PAC’s efforts to defend Death with Dignity in the courts and at the ballot box.

In 1997, the Oregon Legislature, influenced in part by the active stance of the Oregon Catholic Conference, placed Measure 51 on the ballot. If passed by voters, Measure 51 would have repealed the Oregon law.

“Even though I had moved east when it was on the ballot a second time, I was still supporting the PAC’s efforts,” Roberts says. “I again made my endorsement very clear.”

She and 60 percent of Oregon voters celebrated on November 4, 1997, when Measure 51 failed to pass. Frank’s firm belief that Oregonians would support the assisted dying law was again validated.

“When I understood that Frank Roberts was a man before his time, I really came to understand that this wasn’t an issue of controversy, this was a matter of recognizing something ahead of the rest of the population recognizing it,” Roberts says.

“He could see that end-of-life was an issue that was being poorly handled. And the rest of us were a little slower to reach that understanding.”

Continued Advocacy, One State at a Time

Roberts, who moved back to Oregon in 1998, has continued her work to educate legislators and citizens across the country about the Oregon experience, traveling to Vermont and California to testify before legislative bodies. As an experienced legislator, and with broad knowledge of Oregon’s history of the law, Roberts was able to make an effective case for enacting laws in other states.

“I thought about how hard it had been to get the bill through any kind of a system in the Oregon Legislature because politically people were so frightened,” Roberts says. “I knew how threatening that issue was to legislators. Maybe it shouldn’t have been, but it was. When I testified in Vermont and California and when I supported [the End of Life Options Act] in Colorado, it really helped me to understand there was a reason why the legislative process took so long.”

She also notes that many Americans have only recently become more comfortable with publicly addressing death and dying. Part of that, she believes, has to do with the country’s recent history.

A “Culture in Denial” Evolves

“Ours was a culture in denial about death,” Roberts says. “Then 9/11 happened, then school shootings, the Boston Marathon bombing…all of that happened, and it wasn’t in some faraway land where our soldiers were fighting. It wasn’t in a war someplace else on the planet. And it was in every magazine, and it was in every newspaper. And every time you turned on the television for those years, there were funerals and memorials. And there were survivors talking about it and there were widows talking about it.

“The whole country was exposed to death and grief,” she adds. “I think it changed the American people. I think we were suddenly able to talk about it in a different way. We faced it, we were more realistic. Those were painful lessons, but from my perspective important learning opportunities for Americans about how we deal with end of life no matter where it comes from, and and how we deal with grief no matter what the source.”

Roberts says this increased willingness to explore issues of death and dying has in turn led to a notable increase in end-of-life care planning.

“People do more pre-planning now,” Roberts says. We are becoming more accepting of the whole reality of end of life. I think that’s healthy.”

Against the “Slippery Slope”

Still, suspicion of and opposition to Death with Dignity remains strong as manifest in contentious legislative hearings and high-profile campaigns backed by the Catholic Church intent on defeating proposed laws and rolling back existing statutes.

“The issue that’s raised most often about Death with Dignity when it’s being heard in any state in the nation is the issue of what’s called the ‘slippery slope,’” Roberts says. “And it is usually applied to people with disabilities. Well, I’m the wrong person to talk to about that. I have experienced disability with a son and a husband. I refer to those discussions as abuse and cruelty, because they frighten the disability community into thinking that they are going to be put to death because they’re disabled.”

“There’s no legitimacy to this issue,” she adds. “In 20 years in Oregon, no person with a pre-existing disability has ever used the law. Ever.”

Roberts says that data such as that help lawmakers and the general public understand the truth about the law and how it has been used by Oregonians.

“When it was on the ballot both times in Oregon, opponents talked about how Oregon was going to become a death mill, and that thousands of people would come here to die,” Roberts says. “Well, that doesn’t happen. Residency is required, but it’s not just that. It’s that it’s used pretty sparingly.” Since 1997, 1,749 people have had prescriptions written under the law, and 1,127 died after using it.

“The message is that the patient has control. The patient can get the medication and they can use it or they can choose not to use it. And that probably is the most important element of this.

The patient remains in control. Nothing is more important to me than that.

Like many of those who have been involved in the movement for end-of-life choice, Roberts notes that the passage of the Oregon law catalyzed more than just robust conversations about Death with Dignity.

“Hospice use went up; medical training for end of life at our medical schools changed; doctors began to be taught about end of life with a whole other aspect to it,” Roberts says.

Frank’s Legacy

Perhaps the most indelible testament to Frank’s legacy—and the most powerful message for lawmakers unsure about introducing assisted dying bills—is how accepted the Oregon law has become.

“In Oregon, if a politician introduced a bill to take away Death with Dignity, they would never get elected,” Roberts says. “I think that we’ve got to show that it has not hurt the political leaders who have stepped forward and taken that risk, that they have all been re-elected, and it has not taken away their popularity or people’s’ respect for them.”

Roberts says Frank foresaw this shift over a quarter-century ago.

“He saw ahead of us what we would see later: the logic, the compassion, the reality, and the personal sense it made. He wasn’t just being a radical, he wasn’t just being controversial on purpose. He could see what needed to be done.”